Frost pockets: Nature’s hidden chill zones

Author: Sharad Sigdel

Posted on Dec 5, 2025

Category: Faculty of Forestry and Env Mgt

Why frost pockets matter?

Risk on agriculture: Crops in frost pocket zones can suffer damage even when nearby areas remain above freezing temperature. Vineyards, orchards, and vegetable fields are especially vulnerable. Also, even in summer, frost pockets typically maintain lower temperatures, especially during calm, starry nights. These cooler conditions can significantly hinder crop development.

Vegetation patterns: Sensitive plants avoid these zones, while hardy species dominate. As we can see different species of trees dominated even in small, rugged terrains.

Effects on wildlife: Variations in microclimates may influence insect activity, bird nesting, and soil conditions.

Imagine a farmer waking before dawn in late September. He walks down into the valley, expecting dew on the grass. Instead, he finds a thin layer of frost sparkling across his crops — while the hillside above remains untouched. This is the quiet power of a frost pocket, a microclimate that can make or break a harvest.

What are frost pockets?

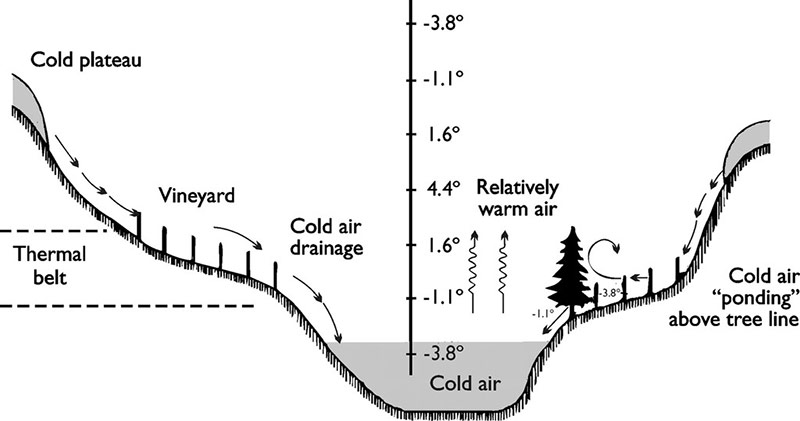

Frost pockets, also called frost hollows, are low-lying areas, valley, depressions where cold air accumulates. As we know cold air is denser than warm air, it flows downwards at night and pools in valleys, hollows, or basins [4].

Formation: During calm, clear and stary nights, the ground radiates heat to the space. The air near the surface cools, becomes denser, and sinks into depressions [5,6].

Temperature inversion: This pooling creates a temperature inversion, where the coldest air is at the bottom, and warmer air goes above. Air pooling causes the tree line to invert.

Timing: Frost pockets are more prominent during early spring and late autumn, when nighttime temperatures fall below freezing. However, even in summer the frost pocket zones are cooler.

Where do they occur?

Mountain valleys: Alpine, alps, Appalachian Apennine, Kent and some local hilly regions in Australia have been reported often dramatic cold-air drainage.

River basins: Mostly river valleys receive and trap the colder air from it’s neighboring up hills. V- shaped narrow valleys trap more colder air than U- shaped valleys [7].

Rural landscapes: Farmers often know the frost spots in their fields from experiences of several years. Occurs mostly on low laying part of the farm.

Global highlights: Extreme air-cooling phenomena

In the Alps of Austria, the most extreme case of air pooling in a mountain valley recorded a temperature difference of up to 27°C [8]. A case study from Ohio, located within the Appalachian Mountain range, observed a 14°C drop in a valley just 70 meters deep [9]. The study also revealed that frost tends to arrive about a month earlier in valleys compared to hilltops. Interestingly, significant temperature variations have also been reported in Prince Edward Island (PEI), Canada. Despite being a relatively flat island, PEI experienced a 6°C drop across an elevation change of only 40 meters [10]. Another report from a Pennsylvania valley indicated a 6.5°C increase for every 100-meter rise in altitude [11]. Similarly, England’s Kent Valley recorded an increase of 4.5°C per 100 meters of elevation gain.

Frost pockets in New Brunswick: My observations

The landscape of New Brunswick varies significantly as you travel across the province. In the northwest, rugged terrain with frequent upslope and downslope contrasts sharply with the flatter areas stretching east from Fredericton toward Moncton and Bathurst. Additionally, the Bay of Fundy region features another mountain range near the coast. Based on our ongoing predictions and global frost pocket data analysis, we developed an equation and applied it to New Brunswick using ArcGIS Pro at 10-meter resolution.

The results suggest that the northwest region and areas near the Bay of Fundy are more prone to frost development compared to the central and eastern lowlands. Frost-prone areas in New Brunswick are primarily concentrated in valleys and river basins. Our analysis is still evolving as we incorporate additional factors, but for now, this represents our preliminary prediction of frost pockets across the province.

References

- Frost pocket image

- How to prevent vineyard frost damage

- What are frost hollows or frost pockets in the mountains

- Raitio, H. (1987). Site elevation differences in frost damage to scots pine (pinus sylvestris). Elsevier science publishers, 20, 299.

- Tabony, R. C. (1985). Relations between minimum temperature and topography in great Britain. In Journal of Climatology (vol. 5).

- Perry, k. (1998). Basics of frost and freeze protection for horticultural crops. Horttechnology, 8(1), 10–15.

- Lindkvist, L., Gustavsson, T., & Bogren, J. (2000). A frost assessment method for mountainous areas. Agricultural and forest meteorology, 102(1), 51–67.

- Pringle, L. (1981). Frost Hollows and Other Microclimates. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company.

- Will, Joshua D., M.A. (2006). Geography Analysis of Nocturnal Temperature Inversions in Meigs County Ohio: An Appalachian Frost Hollow Case Study.

- Hocevar T and, A., & Martsolf, J. D. (1971). Temperature Distribution under Radiation Frost Conditions in a Central Pennsylvania Valley.