Indigenous History Month exhibit bridges past, present and future

Author: Camila Lefebvre

Posted on Jun 21, 2024

Category: UNB Fredericton

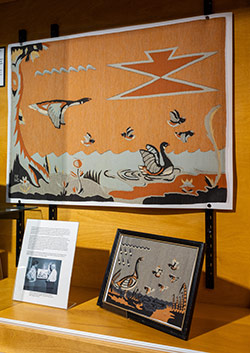

When walking into the display area on the third floor of the Harriet Irving Library, goose feathers in photographed tapestries thread across an amber sky. Soon, the cooling water from within the fabric wraps around you, submerging you in sounds, textures and history. Distantly, you hear the ghostly chirps of the muskrat caller on display, beckoning you to listen, to linger.

This Indigenous History Month exhibit asks for more than just celebration; it demands actively listening, learning, appreciating and sharing Indigenous art, history and ways of being and knowing.

Jesse Simon, assistant director and assistant teaching professor at the Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre (MWC) says the exhibit is intended to amplify the role of Indigenous knowledge and culture in various sectors of the university.

“We [at the MWC] want to make an in-depth contribution, whether that’s through academics, economics or politics. We want to be major players in the game… Right now, we’re looking at expanding so that we can be the heartbeat of the university,” said Simon.

The exhibit was organized through a partnership between Simon and Natasha McAllister, governance and leadership program coordinator at the MWC, Matty Watson from UNB Archives & Special Collections and Mattia Fonzo from the Harriet Irving Library Research Commons. It will be on display until July 2, bringing together a multimedia selection of traditional Mi’kmaq items.

The collection

From the Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre, the exhibit consists of Wihkewi Kisuhs (October) drum from Samaqani Cocahq (Natalie Sappier), a hide scraping tool and hides, a sweetgrass basket and photos of tapestries created by Ivan Crowell, based on artworks by Mike Francis, Simon’s uncle.

From the Archives & Special Collections, several items were made by Peter Paul, a Wolastoqi Elder and expert on Wolastoqey culture. These include a birch bark moose horn and a wooden muskrat caller. Also on display is a Calamus root, collected by Paul. These roots are traditionally used for ceremonial purposes and medicinal effects.

Other items can be found through the MWC’s Wabanaki Collection and the Wolasotoqey language app found at the exhibit.

What was

McAllister explained that an incentive behind building this exhibit was to educate others about the foundational cultural, social and political elements of Canadian society that have come from Indigenous practices.

“We [at the MWC] envisioned a celebration of Indigenous culture, Wabanaki culture and all their contributions so we [could] show how Indigenous people have and continue to influence this space and this land,” said McAllister.

In particular, the drums are inspired by the Thirteen Moon Teachings of Elder Opolahsomuwehs (Imelda Perley), which Samaqani Cocahq (Natalie Sappier) turned into beautiful paintings on the drums’ surfaces. The 13 drums represent 13 moons within the calendar cycle.

“The drums depict sacred teachings about the sacred relationships we hold with ourselves, others and that which surrounds us, as they relate to each moon,” said McAllister. “The teachings act as guides to lead us into better harmony and relationship.”

The tapestries, in turn, have been at the MWC for many generations, as well as part of a recent exhibition at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery.

The book Wabanaki Modern, Wabanaki Kiskukewey, Wabanaki Moderne by Emma Hassencahl-Perley and John Leroux found in this section highlights the work done by Ivan Crowell, a tapestry artist inspired by Mike Francis. The text seamlessly weaves together tradition with the modern art of the Wabanaki people.

What is

The drums are not solely items for display. The drum is regularly implemented in ceremonies of healing, such as sacred fires, talking circles, pipe ceremonies, sweat lodges and within homes for women and families in transition.

“They're not just display items, though they are beautiful,” said McAllister. “They are also conceptualized as healing implements and we honour their spirits through ceremony.”

Elder Opolahsomuwehs (Imelda Perley) brings the drums to communities all over New Brunswick, for baby naming ceremonies, sweat lodge ceremonies and many others.

Additionally, the bone scraper has been used in the MWC’s land-based learning, where they are taught to prepare the hides for drum-making and art projects.

The items at the exhibit defy the norms of typical exhibit displays because the items are currently being utilized by local communities, not simply sitting on a shelf. The exhibit pushes the boundaries of the way culture and tradition can be celebrated.

"We want the students to know they belong here, and it's hard to know you belong when you're tucked up on a hill,” said Mcallister.

”We try our best to reach out to our students with the types of support we provide to ensure that they feel safe and supported and belonging in this community. We must showcase ‘You do belong here. You are part of this wonderful community.’”

What will be

This exhibit is the start of a conversation. Simon expressed that familiarizing the public can be the groundwork for bettering the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

The MWC leadership intends to add the art and academic work of Indigenous scholars and students, highlighting how they contribute to research and contemporary discussions.

In alignment with the philosophy behind this exhibit, initiatives on UNB campuses such as this can generate understanding and space for Indigenous knowledge in all areas of the university and beyond.

Simon, McAllister, Watson and Fonzo foresee the project leading to treaty rights, fishing and forestry education, bridging the history of Indigenous knowledge from the past and present and carrying it into the future well-being of UNB students.

“The philosophy behind [this display] is the more people want to understand, the more people will get into conversations,” said Simon. “Ultimately, [a] bridge [is formed]. If there's misinformation, then we come to share the same information, [in order to] see each other at the same level. We don't have to agree. But if both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people come to a place where they both [try to] understand each other… [our relationships] will be better.”