Heartfelt science: UNB graduate student investigates Arctic fish

Author: Tim Jaques

Posted on May 15, 2024

Category: Research , UNB Saint John

Emily Williams conducts fishy research - and in the best way possible.

Williams, a University of New Brunswick (UNB) Saint John student, has done research into the cardiac responses of certain Arctic fish species to fluctuating temperatures that offers critical insight into their ability to adapt to a rapidly changing climate, with implications for sustainable resource management.

“I’ve always been interested in marine biology, and I completed my undergraduate degree at UNB,” said Williams, who is in the second year of her master’s degree in biology.

“I understand it is essential to integrate lab and field studies because sometimes what you study in the lab does not necessarily apply to the field. It is nice to have both of those create comprehensive research.”

Williams’ field research involves freshwater lake trout and saltwater Greenland cod and fourhorn sculpin in Ikaluktutiak (Cambridge Bay), Nunavut.

She studies seasonal changes in the heart function of the fish and the adaptations that help them cope with temperature shifts. Given global warming in the Arctic, it is essential to know this effect.

“I am looking at those warm temperatures and their peak heart rate. I also look at the temperature at which that peak rate is reached and then at which the heart goes arrhythmic. Arrhythmia (an irregular heartbeat) indicates a heat-induced heart failure.”

If a fish is in water that is too warm, its heart can stop beating.

At the end of each winter and summer, she travels to the North and catches the fish by angling or with gill nets. Electrocardiogram equipment monitors their heart rates at different water temperatures while they are anesthetized, with water flowing over their gills. Small electrodes are inserted under the skin to detect and record electrical signals from the heart.

The research may shed light on how fish can cope with warmer temperatures in the Arctic caused by climate change.

“Some of these fish can adjust to these types of changes, but there are typically limits on their ability to adjust,” she said.

“My results will show how the ability of these Arctic fishes to tolerate extreme temperatures and to regulate their heart function will change from the end of winter, when they are accustomed to the very frigid water temperatures, to the end of summer, when they are more accustomed to warmer water.”

The Greenland cod offered an unexpected finding. In winter, they cannot tolerate higher temperatures, or their hearts will start to fail. In summer, they can tolerate higher temperatures from 15 to 20 degrees, which is surprising as they live in the cold ocean and have never encountered such warmth.

The fish help sustain local populations and Williams worked with area Indigenous groups.

“I have had the privilege to work and learn from several community members. The overarching projects I have worked on have received regular input from the Ekaluktutiak Hunters and Trappers Organization for many years, since the project has been running up there for so long,” she said.

“They’ve shared much of their knowledge on how the environment and temperature changes, and they have noticed things with fish populations and movements.”

Ben Speers-Roesch, an associate professor in the department of biological sciences, is Williams’ co-supervisor along with James D. Kieffer, a professor in the same department. Speers-Roesch said local engagement is important.

“She works directly with Indigenous partners in a spirit of partnership and reconciliation. Inclusion of Indigenous viewpoints and direct collaboration has the benefit of incorporating traditional knowledge into our research and is an important way to bridge the knowledge and experiences of people in the north and south of Canada,” he said.

“Emily is a dedicated science communicator. She is passionate about sharing the excitement and importance of science with the public, including school groups and local communities in the North.”

Williams is the UNB Saint John site coordinator with Let’s Talk Science, which delivers hands-on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) outreach to K-12 students. She has demonstrated basic science at rural and Indigenous schools in New Brunswick and Quebec and found time to work with students when in Ikaluktutiak.

“They could see in detail how the experiment was done and watched the heart rate change throughout the warming process. We also got to do some fun little activities with them, like measuring their heart rate when they are standing versus after they run around for a little bit,” she said.

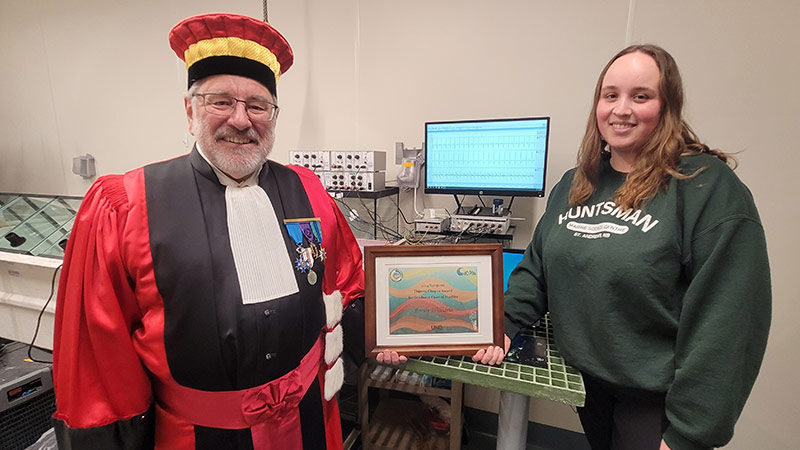

Her communication skills contributed to her recently being awarded the 2024 Thierry Chopin Award for Graduate Coastal Studies for her work.

Dr. Thierry Chopin and Emily Williams.

“She is a very interesting and keen graduate student. She was able to explain her project to me in very simple terms. She is already a very effective and pleasant science communicator,” said Thierry Chopin, professor of marine biology in the department of biological sciences and the award’s founder. It comes with a $500 prize.

Chopin explained that applicants must present their research concisely and demonstrate how it impacts the world outside academia.

“Communicating our science has always been important to me, and we should train the next generation of scientists in that difficult art,” Chopin said.

Williams says her research will contribute to species conservation.

“I see my research as a piece of the bigger picture. It will tell us valuable information on a species’ ability to cope with changing temperatures that can be used alongside other crucial studies to make evidence-based conservation and management choices,” Williams said.