UNB researcher making the world a safer place from chemical weapons

Author: UNB Newsroom

Posted on Jun 16, 2020

Category: UNB Fredericton

It has been 95 years since the League of Nations met on June 17, 1925, to sign the Geneva Protocol, an early attempt to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons in armed conflicts. Nearly a century later, however, their existence continues to be a risk to human security around the globe.

New research out of the University of New Brunswick and the University of Kent (UK) will make it safer and easier to contain and deactivate neurotoxic chemical weapons, like VX and sarin.

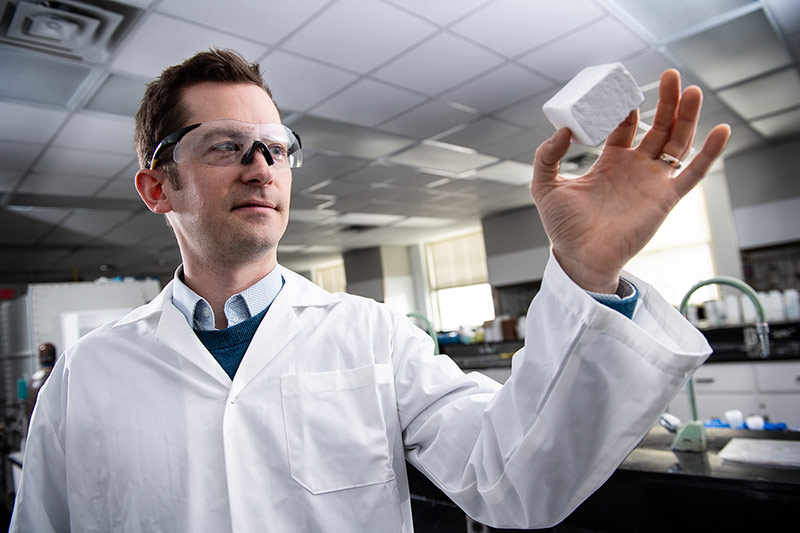

Dr. Barry Blight, associate professor of chemistry at UNB’s Fredericton campus, and Dr. Simon Holder, reader in the School of Physical Science at Kent, have developed new methods to dispose of large quantities of the highly lethal substances.

These chemical weapons, known as organophosphorus nerve agents or neurotoxins, are highly potent, long-lasting, and fast acting. Even minute doses of the chemical disrupt the connection between the body’s nerves and muscles, quickly causing paralysis and death.

Although commonly referred to as gases, the nerve agents are liquids and are aerosolized to affect large areas. They are considered weapons of mass destruction and are banned under international treaties.

“This project is an incredible example of applied science success that we don’t always get to see. It has potential to positively impact the safety of soldiers and civilians around the globe who encounter these chemicals and who work to dispose of them,” said Dr. Blight.

Together, co-principal investigators Dr. Blight and Dr. Holder led a research team that investigated new methods of bulk decontamination of these chemical weapons. Dr. Blight began this research, funded by the UK Ministry of Defence, at the University of Kent. When he moved to Fredericton to take a position at UNB, he continued to work with Dr. Holder, overseeing the project and his researchers remotely.

The team investigated two connected areas of research: first, developing a polymer sponge that would absorb these neurotoxins, rendering them safer to handle and transport; and second, developing an effective catalyst to accelerate the breakdown of the chemical.

The resulting combined material is called an MOF-containing polymer sponge. It consists of a specially created polystyrene sponge that can swell to absorb and contain the nerve agent, and a porous metal-organic framework catalyst, using active zirconia to break down the neurotoxins into biologically inert components.

To safely study the materials, the researchers explored substances that can simulate the presence of neurotoxins without risking exposure to the active agent. After extensive testing with these simulated agents, the UK Defence Science and Technology Laboratory tested the prototype material with the live nerve agent to confirm the real-world response.

“Less than five kilograms of the MOF-containing polymer sponge can absorb, immobilize and safely destroy a 55-gallon drum of these toxic chemicals. It is very exciting to consider the potential this has in combatting dangerous chemicals in the future,” said Dr. Holder, who is also director of research at Kent’s School of Physical Sciences.

Since military personnel are often involved in decontamination and destruction of these chemicals, Dr. Blight hopes to further expand the research in partnership with defence labs in North America.

“For bulk quantities of these horrific materials, no one has ever developed anything like this. I’d like to see us find even easier, faster and cost-effective ways of destroying these materials,” said Dr. Blight.

Dr. Blight and Dr. Holder’s paper has been published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces. Their research was funded by the UK Ministry of Defence, Defence Science and Technology Laboratory.

Media contact: Jeremy Elder-Jubelin

Photo credit: Rob Blanchard/UNB