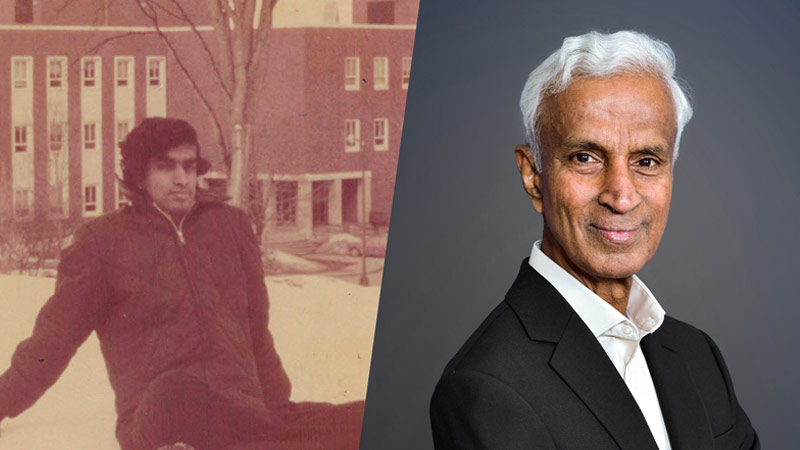

From small choices to global impact: UNB Alum Subramonian Shankar's journey in computing

Author: Alex Graham

Posted on May 29, 2025

Category: UNB Fredericton

On May 29, 2025, UNB alum Subramonian Shankar (MScEng'76) will receive an honorary doctorate of science at the 196th Encaenia ceremony on the university’s Fredericton campus.

It’s the little things that often make the biggest difference in our lives.

For University of New Brunswick (UNB) alum Subramonian Shankar, a seemingly trivial decision by UNB administrators prompted him to take a chance on making a small city on Canada’s east coast his first North American home.

“I wanted to apply to a graduate program in either the United States or Canada, and I was looking for universities which would not require an application fee,” he said with a laugh.

In the mid-1970s, UNB was one of the handful of North American post-secondary institutions that did not require an application fee.

“I was in India at that time, and even if I could save $10, that was a big sum for me. So, I said, ‘OK, let me try UNB.’”

That fateful decision shaped not only Shankar’s life, and the lives he touched during his time at UNB’s electrical engineering program, but has had an impact on nearly every person who has used a computer.

As the founder of American Megatrends Inc. (AMI), Shankar has personally helped shape the hardware and software of every computer in the world.

The big decision to start his own company came about because of many smaller decisions, all of which started at UNB.

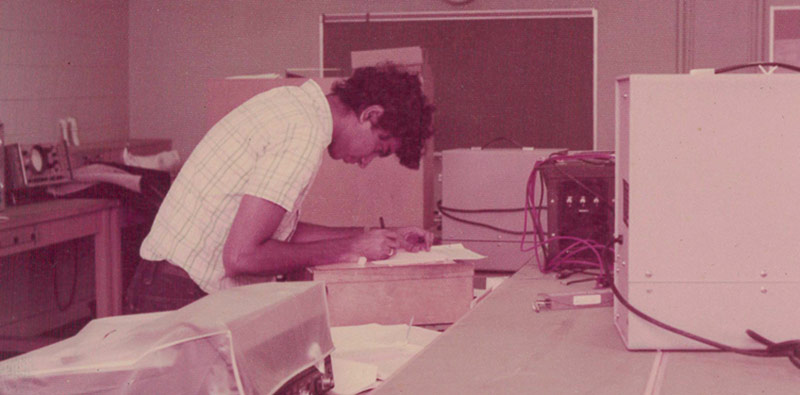

“Prior to coming to UNB, I’d had very little exposure to computers,” Shankar said.

“The use of computer programs to answer some of the problems that I was trying to answer in my thesis was probably the most exciting part.”

Using the computer programming language APL (array-oriented programming language), Shankar applied his newfound knowledge of computers to his thesis, using computer-aided graphics.

“Computer programming, using computers, applying it to my thesis and being able to solve some of the problems … probably without computers I would not have been able to do my thesis work,” he said.

“And it turns out what I did was pretty interesting. At least, that’s what my supervisor told me at the time,” he joked.

Picking up and moving halfway around the world is a daunting task, but Shankar said even back in the mid-1970s, UNB was reaching out to the world and beginning to build its international network.

There was a small but mighty international community on campus at the time, including an active international student association with several Indian students Shankar said were his support network.

He recalled that time fondly, when he made connections not only with other international students, but also with the tight-knit Indian community in Fredericton.

“They were very friendly and helpful,” he said. “We could visit them during the weekends.”

After finishing his degree, Shankar tried his hand at a few opportunities before realizing his dream of setting off on his own.

He ventured to the United States and worked in the computer industry for a time, then returned to India to continue his work. As often happens in newly emerging economic spaces like tech, the company he was working for went bankrupt and he was once again faced with a decision to make.

“I was at kind of a crossroads, wondering what to do next,” he said.

A friend he’d kept connected with from his time in the U.S. encouraged him to return stateside.

“He told me that with the kind of work and background knowledge that I have, maybe I should start a company. He encouraged me.”

Shankar decided to give the U.S. one more shot. Although he considered striking out on his own, he initially tried to find work with an established company.

“It was not easy to find a job,” he said of the conditions in Georgia’s technology sector in the early 1980s. “I thought the best thing to do was to start my own company and employ myself. And after that, it was pretty easy because I had a good understanding of PCs (personal computers). I knew exactly how they worked, how to design them. All I had to do was to pick up some particular product area and get going with it.”

Picking an area to excel in was another significant choice for Shankar, and in the end AMI produced many important hardware and software products, some of which still resonate in the computing world today.

Of all the products AMI produced, Shankar says the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) stands out for him. This firmware interface performs tasks like loading the operating system, managing memory and storage and allowing users to configure system settings. The success of BIOS led to a further evolution of the product called Aptio which is a continuing standard in the industry today.

Now in his early 70s, Shankar has embarked upon what might be his most significant decision yet. Retired from AMI, he launched the Lakshan Foundation which has allowed him to work with the institutions that gave him his start in the 1970s.

At UNB, the Shankar Computer Science Laboratory provides 74 state-of-the-art, on-campus workstations, as well as 70 additional machines that allow students to access the lab’s significant resources remotely.

Shankar said he was delighted to hear from UNB that the lab is having an impact on students and their ability to learn the craft of computer engineering and software development at the highest level.

“My goal was to see what I could do to benefit as many students as possible.”